#ernest d farino

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Steel and Lace (1991)

Do you remember that scene in RoboCop where RoboCop shoots a rapist in the dick? RoboCop nails the guy perfectly through the thighs and skirt of a would-be victim, doubly traumatizing her before ineffectively referring her to a rape-crisis center so he can swiftly move on to enacting more police-state violence elsewhere on the streets of Detroit. The straight-to-video sci-fi slasher Steel and…

View On WordPress

#brandon ledet#Bruce Davison#Clare Wren#David Naughton#ernest d farino#horror#rape revenge#reviews#sci-fi#sci-fi horror#Stacy Haiduk#steel and lace

0 notes

Text

Steel and Lace (Ernest D. Farino, 1991)

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Steel and Lace (1991) Fries Entertainment Dir. Ernest D. Farino

#steel and lace#1990s science fiction#1990s horror#clare wren#decapitation#practical special effects

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

DREAMSCAPE (1984) - Episode 202 - Decades of Horror 1980s

“Mm, I see. So, Jane, what you do here, in effect, is count boners.” Will one hand be enough? You know. The fingers. Will the fingers on one hand be enough for counting? Join your faithful Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, Crystal Cleveland, and Jeff Mohr – as they dream a little dream with you and the star-packed cast in Dreamscape (1984).

Decades of Horror 1980s Episode 202 – Dreamscape (1984)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

A man who can enter and manipulate people’s dreams is recruited by a government agency to help cure the President of the United States of his nightmares about nuclear war but stumbles upon an assassination plot

Director: Joseph Ruben

Writers: David Loughery, Chuck Russell, Joseph Ruben (screenplay); David Loughery (story)

Music: Maurice Jarre

Cinematography: Brian Tufano

Film Editing: Richard Halsey

Special Effects & Makeup:

John Eggett (special effects coordinator)

Craig Reardon (special effects)

David Robert Cellitti (special makeup effects artist)

David B. Miller (special makeup effects)

Visual Effects:

Jim Aupperle (stop-motion visual effects supervisor)

James Belohovek (miniature constructor)

Beverly Bernacki (optical lineup)

Stephen Czerkas (stop-motion crew & snakeman model builder) (uncredited)

Linda Drake (stop-motion crew) (as Linda Obalil)

Ernest Farino (stop-motion crew) (as Ernest D. Farino)

Rocco Gioffre (matte artist)

James Hagedorn (optical printer operator) (as James R. Hagedorn)

Pete Kozachik (stop-motion crew)

Peter Kuran (visual effects creator)

Kevin Kutchaver (special photography)

Dennis Pies (dream tunnel effects created by)

R.J. Robertson (rotoscope animation)

Paul Sheppeck (additional matte paintings)

Susan Turner (miniature supervisor) (as Susan K. Turner)

Cast

Dennis Quaid as Alex Gardner

Max von Sydow as Dr. Paul Novotny

Christopher Plummer as Bob Blair

David Patrick Kelly as Tommy Ray Glatman

Kate Capshaw as Jane DeVries

George Wendt as Charlie Prince

Eddie Albert as The President

Peter Jason as Roy Babcock

Chris Mulkey as Gary Finch

Larry Gelman as Mr. Webber

Cory Yothers as Buddy

Redmond Gleeson as Snead

Jana Taylor as Mrs. Webber

Dreamscape is a Decades of Horror 1980s double-tap, first covered in episode 100 by Doc Rotten, Christopher G. Moore, and Thomas Mariani. This time around, Dreamscape is Bill’s pick and he was sucked in by the glowing nunchucks in ads. Although the cast is great, it doesn’t hold up as much as Bill wishes it did and it is far too obvious who the bad guys are. Having said that, it is still a very 80s movie and he would like to see it remade.

Chad thought Dreamscape was great at the time and he still enjoys it even though not everything holds up. In his view, it was hard to pull off everything they were trying to incorporate with the budget they had to work with it. On the other hand, Crystal thinks Dreamscape holds up just fine and she rewatches frequently. Even so, she too would like to see it remade. Jeff still really, really likes it and loves the melding of stop motion animation and other practical effects. He doesn’t appreciate Dennis Quaid’s girl-killer smile but otherwise thinks the cast is incredible.

Regardless of whether or not you’re in the “holds up” or “doesn’t hold up” camps, Dreamscape is a fun 80s flick that tries hard to be a lot of things. At the time of this writing, it’s available to stream from Tubi and Kanopy, and on physical media as a Collector’s Edition Blu-ray from Shout Factory.

Every two weeks, Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1980s podcast will cover another horror film from the 1980s. The next episode’s film, chosen by Crystal, will be Howling II: … Your Sister Is a Werewolf (1985), also known as Howling II: Stirba – Werewolf Bitch. Discussing this masterpiece should be howling good fun. …sorry.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the gruesome Magazine Youtube channel, on the website or email the Decades of Horror 1980s podcast hosts at [email protected]

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Photo

Next week marks the home video release of KONG: SKULL ISLAND (2017, Dir. Jordan Vogt-Roberts) and to celebrate I’m going to be posting an updated version of an article I originally wrote for Kevin Derendorf’s fantastic blog Maser Patrol back in March in anticipation of KONG: SKULL ISLAND’s then impending theatrical release. As recounted on the KONG: SKULL ISLAND episode of the Maser Patrol Podcast (on which I also appeared), Kevin originally asked me to write something for the blog on account that I was currently teaching a course on King Kong and Western History and Culture. Initially I was unsure of what I could contribute until the subject of Delos W. Lovelace’s 1932 novelization of the original KING KONG (1933, Dir. Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack) was broached. Having long been fascinated with the novelization of King Kong for reasons which should quickly become apparent I set to work writing an admittedly lengthy essay outlining both the history of the novelization’s conception and publication as well as the major differences between it and the final theatrical film. This proved to be a rewarding experience since shortly after the publication of my article I was contacted by Ernest Farino of Archive Editions LLC; the publisher of Mike Hankin’s exhaustively researched 3-volume series Ray Harryhausen - Master of Majicks, the first volume of which had proven an important source when researching the history of Lovelace’s King Kong novelization. Ernest was kind enough to share with me some incredibly rare and hard to come by documents and information regarding the different prose versions of King Kong that have been printed over the years as a result I have updated this essay to reflect, what are for me, new discoveries. This updated version of my essay is also coming into existence in a post-KONG: SKULL ISLAND world. When I originally wrote this article I had no idea that an exhaustive essay on the 1932 novelization of the original KING KONG would be so relevant to this latest Kong film, but it was, and so again this essay has been updated to reflect that. With all this out of the way here is…. KING KONG (1932) THE DELOS W. LOVELACE NOVELIZATION (2nd Ed.) Though often considered ‘junk literature,’ movie novelizations – that is, novels based on film scripts – remain a popular and lucrative part of the modern American literary landscape. According to Randall D. Larson’s authoritative book Film Into Books: An Analytical Bibliography of Film Novelizations, Movie and TV Tie-Ins, novelizations are as old as the cinema itself. Historically studios commissioned novelizations as another way of drumming up advance publicity for a film, as well as to provide their movie with a more erudite air at a time when films were still seen as a gimmick by many and not deserving of the same cultural status as books. Also in the days before home video and television, novelizations served as a way for people to revisit a beloved film. Today novelizations remain popular because they often provide fans with a more complete version of a particular story then what can be found in the two-hour runtime of a film. Characters that only got a few words in edgewise can monologue for pages, and various bits of narrative minutia can be expanded upon at length. And because novelizations have to be written well in advance of the film itself being finished, novelizations will often contain deleted or alternate versions of certain scenes not found in the theatrical release.

With regards to Delos W. Lovelace’s 1932 novelization of the 1933 version of King Kong, all of the above is true and then some, because part of what makes Lovelace’s novelization of the original King Kong so interesting is not just the more fully fleshed out characters or the numerous scenes found within the book but not the film, but the fact that Lovelace’s novelization is one of the very few which has never gone out of print – at least not for long. Casualties of their very nature, most movie novelizations are printed once, sold briefly and then disappear entirely; only to pop-up later on the collector’s market where they go for exorbitant prices. Only a lucky few – such as the novelizations for the original Star Wars Trilogy or Alan Dean Foster’s novelization of Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) – stay in print perpetually. Lovelace’s King Kong is one of these.

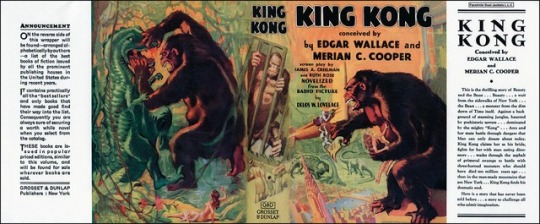

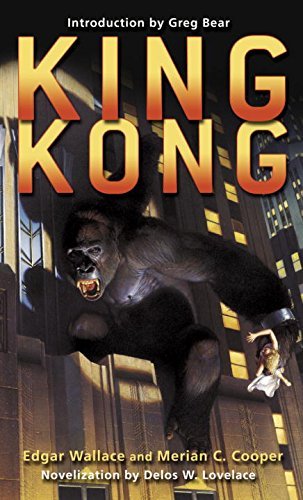

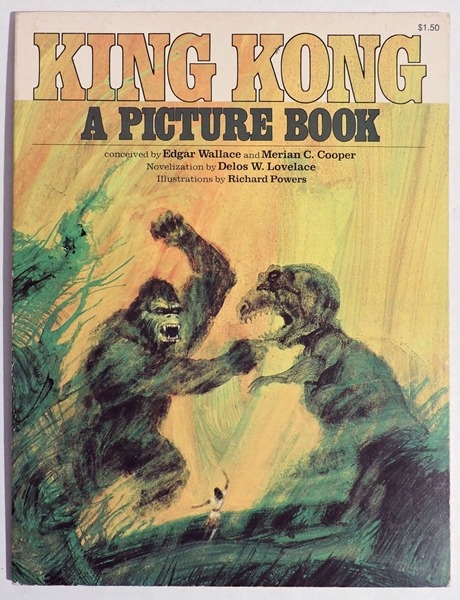

King Kong was originally published in 1932 by Grosset & Dunlap and genuine first editions are identifiable thanks to a typo on the dust jacket where the word “by” is repeated twice (see above image). After this the novel briefly fell out of print until 1965 when it was reprinted by Bantam Books, followed by Ace Books in 1976 with a cover by legendary fantasy painter Frank Frazetta. That same year King Kong was also reissued by Albin Michel, Tempo Books and its original publisher Grosset & Dunlap this time with the later two featuring accompanying interior illustrations by artist Richard Powers. The following year Grosset & Dunlap reissued the book again as did publishers Arthur Barker, Futura and Otava. King Kong then briefly falls out of publication again until 2005 when Grosset & Dunlap reissue the novelization. That same year King Kong is also inducted into the prestigious Modern Library series, with this being the version still on the commercial market today. This edition features a new preface by Cooper biographer Mark Cotta Vaz and an introductory essay by noted sci-fi author Greg Bear, whose 1998 novel Dinosaur Summer – a sequel to Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World set in the early 1950s – I would be remise to not mention here only because it features Merian C. Cooper, Ernest Schoedsack, Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen as strong supporting characters.

Undoubtedly much of the King Kong novelization’s success is owed to its author, Delos W. Lovelace, whose clear, crisp prose and taut pacing make the book an exciting and fast read. However, over the years there has been some confusion as to who exactly Mr. Lovelace was, with some even assuming that he was actually a pseudonym for either best-selling mystery writer Edgar Wallace or director Merian C. Cooper whose names also routinely appear on the novelization’s cover. To clarify this issue, Cooper originally hired Edgar Wallace to write the initial story treatment for King Kong and had also planned to hire him on as the writer of the novelization. However this was not to be as Wallace succumbed to pneumonia complicated by undiagnosed diabetes and died shortly after Cooper hired him and before he could contribute – to quote Cooper himself – “one bloody word” to King Kong. However out of respect to Wallace, and out of a less respectful desire to exploit the late author’s brand name, Cooper gave Wallace story credit on both the film and novelization anyway and also authorized for an abridged version of the novelization to be run in the February and March 1933 installments of Mystery magazine; the publication where much of Wallace’s work had seen print. This Mystery magazine version was simply titled Kong and was published under Wallace’s name alone though it was actually written by Walter F. Ripperger. Cooper then hired his old friend, journalist turned short-story writer Delos W. Lovelace to pen the actual novelization. Cooper had roomed with Lovelace in college and both men worked together as journalists for The Minneapolis Daily News in 1916. As a result Lovelace became the natural candidate to transform Cooper’s movie into a book. Lovelace was paid a total of $600 for his work on the novelization – a significant sum of money in the 1930s – with a contract signed for royalties up to $1,500, after which amount all profits would be split equally between Lovelace and the other “authors”; i.e. Cooper. According to researcher Ray Morton, Lovelace based his novelization off of screenwriter Ruth Rose’s first draft of the King Kong screenplay, which was itself a revised version of the screenplay penned by screenwriter James Creelman who had rewritten Wallace’s initial story treatment. As a result Lovelace’s novelization contains several scenes, a good bit of dialogue and a few more superficial details not found in the final theatrical version of King Kong released in 1933.

Since it is these alternative bits of info which are most likely of interest to readers of this article who have themselves not read Lovelace’s novelization, the remainder of this essay will list the major differences found between the 1932 novelization and the 1933 film version – which I am assuming all readers are thoroughly familiar with. As a final note, there are conflicting reports as to what the legal status of Lovelace’s novelization actually is. Some sources claim that the novel is now in public domain while others dispute this while still other sources say that it is the Mystery magazine version which is public domain while yet others claim it is both. Whatever the case may be one thing is clear and that is that Lovelace’s novelization has proven a source for every major remake, reboot and adaptation of King Kong to come along since the original 1933 film was released. This includes Dino De Laurentiis and John Guillermin’s 1976 King Kong remake, as well as Peter Jackson’s 2005 version and the most recent iteration; Jordan Vogt-Robert’s Kong: Skull Island which is part of Legendary Picture’s MonsterVerse. In addition, both Gold Key and Monster Comics – an imprint of Fantagraphics Books – have produced comic book versions of King Kong based on Lovelace’s novelization in 1968 and 1991 respectively. There have also been animated versions of King Kong as well including 1998’s The Mighty Kong and an episode of the 1990 animated series Alvin and the Chipmunks Go to the Movies, among others, which have clearly used Lovelace’s novelization as a source of inspiration. As a result I have made notes in the following of when and where elements of the King Kong novelization turn up in other Kong media…

· A Ship by Any Other Name: In Lovelace’s novelization the ship Denham and co. take to Kong’s island is the Wanderer, not the Venture as in the movie. In Kong: Skull Island, a ship called the Wanderer is found in the native village where it has been converted into a shrine for Kong. Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts has said that this was done so as to suggest that some variation of the storyline from the original 1933 film was cannon with Legendary Picture’s MonsterVerse.

· Denham, Who?: Actor Robert Armstrong played movie mogul Carl Denham in the 1933 film, but in Lovelace’s 1932 novelization the character is just called Denham with no first name. This is one of the surest signs that you’re dealing with a Kong adaptation that is using the novel as its basis and includes both the 1968 and 1991 King Kong comic adaptations and 1998’s The Mighty Kong.

· The Wanderer’s Crew: Other than Englehorn and Jack we don’t get to know much of the ship’s crew in the 1933 King Kong film. But in Lovelace’s novelization we are introduced to two additional characters; Jimmy and Lumpy. Lumpy is a veteran sailor who spends his time hanging out with a pet monkey named Ignatz. Lumpy never ventures into the interior of Kong’s island and so survives his time there. Jimmy, on the other hand, is a cabin boy who volunteers to go with the first wave of men after Ann and who carries the backpack full of gas bombs smuggled onto the island by Denham. Jimmy later dies in the Spider-Pit. Both of these characters are featured in Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake of King Kong with Jimmy being portrayed by actor Jamie Bell and Lumpy by actor Andy Serkis who pulled double duty as the motion-capture actor for Kong. In Jackson’s version Lumpy dies in the Spider-Pit while Jimmy survives but is badly injured by Kong. Jimmy also pops up in 1998’s The Mighty Kong now with a pet monkey named Chip.

· Ann and Jack’s Backstory: Like the rest of the characters we learn only the scantest details about our principal protagonists Ann Darrow and Jack Driscoll in the 1933 film. Lovelace’s novelization fleshes these two out telling us that Ann was raised on a farm and loss her parent’s at a young age. The money left to her was entrusted to an uncle until she came of age, but her uncle squandered the money leaving Ann destitute and in New York searching for work. Likewise we learn that Jack ran away from home to avoid going to college, became a sailor and later reconciled with his mother – though she disapproves of his association with a known risk-taker like Denham.

· Love in the Crow’s Nest: In the 1933 film Jack confesses his love to Ann on the desk of the ship, but in Lovelace’s novelization he does it up in the ship’s crow’s nest – which is a far more atmospheric and romantic image.

· Skull Mountain Island: Though it may come as a surprise to many, Kong’s home is never actually called “Skull Island” in the original 1933 film. Nor is it called this, per se, in Lovelace’s novelization where it is instead referred to as “Skull Mountain Island.” The name Skull Island appears to go back to Kingsley Long’s serialized version of the King Kong story (to be discussed in more detail below) but it is not until 1976 that the name Skull Island appears in association with any official King Kong merchandise, in this case the John Barry soundtrack for the Dino De Laurentiis and John Guillermin remake; though again the island itself is never called this in the actual film. Since then Kong’s home has been unambiguously referred to as Skull Island in all other movies.

· Racism: As a franchise King Kong has a poor track record when it comes to depictions of both people of color and indigenous cultures. Lovelace’s novelization is no exception here, though it does fair better in some ways and worse in others. For one Charlie the racially insensitive comic relief Chinese cook from the 1933 film – and its sequel Son of Kong – is nowhere to be found. The Skull Mountain Island natives however are still the same lamentable stereotypes with Lovelace contributing a few cringe worthy lines regarding both the white explorers “racial superiority” and how “primitive minds” find the act of thinking especially difficult. Lovelace also chooses to repeatedly emphasize the whiteness of Ann’s skin to a point that it becomes apparent he is attempting to make a link between white skin, virginal innocence and moral purity – ideas which have a long history of problematic racial and sexual connotations.

· The Protagonists Figure out What Kong is Before Ever Seeing Him: After their initial encounter with the natives of Skull Mountain Island, Denham, Jack and Ann return to Englehorn’s cabin and try to make sense out of the mysterious ritual they’ve just seen. Knowing that the native girl they saw was intended as the bride of Kong the four attempt to figure out just what Kong is leading to the following exchange…

“But even agreeing to all this,” Englehorn puzzled, “I haven’t yet any clear idea of what Kong is.”

“I have,” Denham said with abrupt conviction. “That wall wasn’t built against any pintsized danger. There were a dozen proxy bridegrooms because only with so many could the natives approximate the size of the creature which was getting the sacrifices. And those gorilla skins that the dancers wore didn’t mean that Kong is a gorilla by a long shot. If he’s really there, he’s a brute big enough to use a gorilla for a medicine ball.”

“But there never was such a beast!” Ann laughed uncertainly. “At least not since prehistoric times.” Denham shifted in his seat to stare.

“Holy Mackerel!” he whispered. “I wonder if you’ve hit it, Ann?

”“Rot!” Discroll exploded. Englehorn shook an unbelieving head…

“Why shouldn’t such an out-of-the-way spot be just the place to find a solitary, surviving prehistoric freak?” [Denham’s] eyes flashed. “Holy Mackerel! If we find the brute, what a picture!”

· Triceratops in the Asphalt Pit: Marian C. Cooper met Willis O’Brien while the later was at work on never-to-be-completed ‘Lost World’ picture Creation. At the time the only sequence from Creation which O’Brien had committed to film was a brief scene in which a hunter shoots and kills a baby triceratops, enraging its parents who proceed to chase the vandal down and gore him to death. Cooper had originally intended to make use of this footage and O’Brien’s triceratops models in a sequence following the crew of the Wanderer’s narrow escape from the lagoon dwelling brontosaurus. In Lovelace’s novelization the men catch up with Kong who is embroiled in a fight with a trio of triceratopses in an asphalt pit with Kong lobbing boulders at his dinosaur adversaries. Kong escapes the enraged dinosaurs that then turn their attention to the men and give chase, killing one, while the rest are forced onto a log leading across a ravine where they encounter Kong on the other side. It’s not clear at what point this sequence was cut from the 1933 film but it seems to have been fairly late and after having gone through several variations including one where the triceratops would be replaced by a prehistoric rhino – arsinoitherium – and another in which they were replaced by a different horned dinosaur; styracosaurus. Early publicity photos of the iconic log sequence exist showing the styracosaurus on the one side of the ravine and Kong on the other. Some, like Peter Jackson, believe a version of this scene, like the infamous ‘lost’ Spider-Pit sequence, may have even been shot and then deleted. Variations on this sequence show up in both the 1968 and 1991 King Kong comic adaptations. In the 1968 comic Kong battles a pair of triceratops while a styracosaurus chases the men across the log. The 1991 comic has Kong facing off against a whole heard of different ceratopsian dinosaurs and a random ankylosaurus(!) In 1998’s The Mighty Kong the stegosaurus the sailors initially encounter in the 1933 film is replaced with a lone ceratopian, anticipating Peter Jackson by seven years. A triceratops skull is also featured prominently in the mass grave seen in Kong: Skull Island, which director Jordan Vogt-Roberts says was done to indicate that while dinosaurs did once exist on Skull Island that by the 1970s they are all long dead.

· The Spider-Pit Sequence: Undoubtedly the most celebrated deleted-scene of all time is the infamous Spider-Pit sequence. Conceived early on in the 1933 film’s development this sequence would have taken place immediately after Kong knocks the remaining sailor off the log into the ravine. The sailors – most of whom are still alive – would have awakened to find themselves besieged by various giant arachnids, insects, lizards and other assorted monstrosities who lurk at the bottom of the ravine. Behind-the-scenes photos from the 1933 film show that the set and models for the scene were constructed but to this day debate rages over whether or not they were ever actually employed with many fans holding out hope that they were and that the deleted scene has survived the ravages of time locked away somewhere in an unmarked film canister waiting to be rediscovered. This sequence however definitely shows up in Lovelace’s novelization and is just as chilling as anyone might hope. It also shows up in 1991 King Kong comic adaptation and, of course, in Peter Jackson’s 2005 film. Jackson also commissioned a period-accurate reconstruction of the original Spider-Pit sequence which is included as a special feature on all current Blu-ray and most DVD releases of the original King Kong. Spiders are, of course, not the only denizens of the Spider-Pit and one of these beasts did make it into the 1933 film. This is a strange two-legged lizard which climbs up the side of the ravine in an attempt to get Jack. Identified as a fictitious “polysauro” in the Draycott Montagu Dell version of the King Kong story (to be discussed in more detail below) this creature also served as the principal inspiration for the Skull Crawler kaijū in Kong: Skull Island.

· Kong vs. a Giant Snake (Maybe?): Following his fight with the tyrannosaurus, Kong reaches his mountain lair where he encounters another foe lying in wait. Based on Lovelace’s description it’s not entirely clear what this creature is supposed to be though it is described as “serpentine” leading many subsequent artists and filmmakers to conclude that it is a giant snake. This includes most notably Dino De Laurentiis and John Guillermin in their 1976 King Kong remake as well as the artists for the 1968 and 1991 comic book adaptations, 1998’s The Mighty Kong and even the “Kong!” episode of the 1990 animated series Alvin and the Chipmunks Go to the Movies. In the 1933 film version of this sequence the creature Kong battles is actually an elasmosaurus; albeit an admittedly snake-like one.

· Escape from Kong’s Lair: In the 1933 film Ann and Jack escape from Kong’s lair by attempting to shimmy down a vine dangling over a cliff. When this doesn’t work the two jump into a pool of water below. In Lovelace’s novelization, however, Ann and Jack escape by diving down into the pool inside Kong’s cave – the same pool the giant snake had been hiding in – and swimming through an underwater tunnel and that spits them out over the adjacent waterfall. The two then swim down river until reaching the lagoon where the crew of the Wanderer previously encountered the angry brontosaurus and then running the rest of the way back to the native village.

· Kong Caged: Lovelace describes Kong as being shackled to the floor inside a large cage when he is presented to the public as part of Denham’s show, as oppose to the now iconic crucifixion pose from the 1933 film. Both the 1968 comic adaptation and Dino De Laurentiis and John Guillermin’s 1976 King Kong remake share the cage imagery.

· Kong in New York: In Lovelace’s novelization Kong pursues Ann and Jack into the lobby of the hotel where Jack is staying which is across the street from the theater – Ann had the good sense to get a room nine blocks away – where a security guard opens fire on the beast-god with little effect. In the 1933 film Kong climbs the building searching for Ann and in one of the more horrific scenes finds another woman sleeping in bed. Thinking it may be Ann, Kong reaches inside of picks her up. When he realizes it is not he simply drops her to her death. In Lovelace’s novelization this moment still plays out but is surprisingly more terrifying since it occurs from Ann and Jack’s perspective who can only hear what is happening to the women in the room next door to them. Once Kong has Ann he escapes by climbing over various NYC rooftops until he reaches the Empire State Building. Unlike the 1933 film there is no sequence in which Kong destroys an elevated train.

· “It Was Beauty. As always, Beauty killed the Beast:” Denham still delivers a slightly wordier version of his famous last line in Lovelace’s novelization from atop the Empire State Building rather than on the ground next to Kong’s body as in the film.

Lovelace’s novelization is not the only prose version of the original 1933 King Kong film to appear in print, though it is definitely the most accessible today. The aforementioned Mystery magazine version of the story has been reprinted in Mike Hankin’s Ray Harryhausen - Master of the Majicks Vol. 1: Beginnings and Endings. Forest J. Ackerman, founder of Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine also later rewrote the Mystery magazine version when he serialized it in Issues #25-27 (Oct. 1963-March ’64) of his now legendary fanzine. Ackerman evidently felt that “many of the ‘good’ parts were left out” in this adaptation (he’s right, there’s no T. Rex fight for one) and so Ackerman took the liberty of adding them back in.

Hankin also reports that beginning in April of 1933 the London Dailey Herald ran a serialized version of King Kong over the course of 37 installments penned by journalist turned crime-fiction novelist Kingsley Long. Long’s version of the story – which is virtually impossible to come by today with one of the few extant copies kept under lock-and-key at The Special Collections Library at Brigham Young University – is told in a pseudo-documentary style; reporting on the events of King Kong as if they had actually happened. Hankin writes that Long’s adaptation not only fleshes out the principal characters more but also contains such intriguing additional information including the idea that “the origins of Kong and the Skull Island civilization” lie in Atlantis – an idea that crops up in Weta Workshop’s faux-field guide The World of Kong: A Natural History of Skull Island and finds its fullest expression in the 2005 direct-to-DVD animated movie Kong: King of Atlantis – and reveals what happened to Kong’s body after his fall from the Empire State Building: Denham had it stuffed and mounted and charged folks to see it!

Yet another short-story version of the film appeared in the October 1933 issue of Cinema Weekly magazine where it was also credited to Edgar Wallace but actually written by Draycott Montague Dell. This adaptation was later reprinted in the 1988 book Movie Monsters published by Severn House and is now out-of-print, though it appears to be common throughout public libraries and used copies are not hard to track down. That same month this same version of the story also appeared in the juvenile publication Boys Magazine (Vol 23. No. 608, Oct. 1933).

There has also been at least one children’s book adaptation of the original King Kong. First published in 1983 and then again in 1988 by Random House this version was based on the Lovelace novelization but rewritten for children by Judith Conaway with accompanying illustrations by Michael Berenstain. Conaway was not the last to rewrite Lovelace’s prose however. In 2005 writers Joe DeVito and Brad Strickland also rewrote Lovelace’s 1932 novelization and published it under the title Merian C. Cooper’s King Kong: A Novel. The point of this was apparently to improve upon Lovelace’s original as well as to bring the novelization into the same narrative continuity as DeVito and Strickland’s own original prequel Kong novel Kong: King of Skull Island.

#king kong#delos w. lovelace#kong: skull island#novelization#jordan vogt-roberts#stop motion animation#stop motion#dinosaurs#dinosaur#kong

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

i found at that john carpenter's the thing had storyboards and they're on the fan website

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Steel and Lace#Ernest D. Farino#Clare Wren#Bruce Davison#Stacy Haiduk#1991#VHS#computer#wireframe#cyborg

392 notes

·

View notes

Photo

121 notes

·

View notes

Photo

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Steel and Lace (Ernest D. Farino, 1991)

35 notes

·

View notes